At the same time as various measures were being implemented by the state authorities, with the compliance of the Mission, to get the Tater people to give up their travelling lifestyle, there were rules introduced in various municipalities that made it difficult for Tater people to settle (Møystad 2008 and 2015). It was precisely because of the municipalities’ opposition to Tater settlement in their communities that the authorities adopted state regulation of the "vagabond problem”.

Some of the same municipalities that suggested to the Storting that the Tater people should be refused horse-husbandry were also behind restrictions that would prevent Tater people from settling in their communities. Våler, Åsnes and Grue had in many ways a common policy toward Tater/Romani people. The aforementioned joint meeting on the Tater issue in 1946 confirms this, and it was animal welfare associations in Solør that raised the issue of horse-husbandry prohibition for “vagabonds”.

Våler, Åsnes and Grue are located in an area where many Tater people have stayed over the years. News stories from the period 1945 to 1970 confirm that people of Tater descent who wanted to settle permanently in these municipalities faced stern opposition from municipal authorities.

This also confirms the stories people have told about themselves or relatives being refused permission to buy a house or a building plot, or being refused a concession to purchase land.

A review of news stories from other parts of Norway, however, shows that these policies was not unique to these three Hedmark municipalities. The same discussions in other municipalities appear in Norwegian newspapers from 1945 to 1970.

The debate about the settlement of the Tater people reflected a prolonged discussion in many communities about how the people should be treated. At a time when many Tater people wanted a permanent place to live, they were met with prejudice, discrimination and bans in many communities.

This also demonstrates that their travelling lifestyle was not necessarily voluntary. "We didn't leave, we were chased", many Tater people say. The practice of "chasing the Tater people from village to village" has been described as a persistent feature of Norwegian society's behaviour toward this people. Tater people who wanted to settle in a village and those who tried to get their children into the local school experienced the mobilisation of neighbours or of entire communities to prevent them from settling down.

The story below, which is from 1953, touches on what could happen if someone of Traveller heritage wanted to buy a house or a plot.

Karl explains

"My parents always rented our house. Buying a house wasn't easy. After the war, they finally bought a house in Våler. No one could deny them because they had the right of municipal domicile there after Milla."

"It was almost impossible to rent a house from the buros (the residents). Once I grew up and got married, we eventually rented an old, run-down house where we lived for three years. We got to know the neighbours well. One of the families was particularly friendly. They loved children, and ours ran in and out of there."

"After a while, we wanted to buy a house, but this turned out to be difficult. In Åsnes, they had decided that no Tater people would be allowed! We had to resort to trickery to buy a plot. The plot was initially purchased in the neighbour's name, then later sold to me! At the magistrates’ office, their jaws dropped when my neighbour told them the deed should be in my name. 'How can you sell a plot to these people?', was the question he was asked!"

"When I was going to start building on the plot, I went to the bank to get a loan. There they said: 'You're an honest guy, Karl, so you'll get a loan.' I was offered a loan of NOK 5000, but I didn't dare borrow the whole amount. I helped with the carpentry, so it cost only NOK 600. Getting a new house was heaven for us. It was something that we weren't very accustomed to. After a while, we wanted to divide the plot so we could build a garage, like our neighbours did. But unlike our neighbours, we had to wait."

"One of the neighbours tried to get us to move. She launched a petition stating we were unwanted as neighbours, but she didn't get very far. No one would sign. It also turned out that we were the only ones in the neighbourhood who had paid cash for the plot. Otherwise, people have been pretty nice to us here in Åsnes. The ones in control in Åsnes have not been."

(Karl, born 1934)

Newspaper articles in the local press about the settlement of the Tater people in Åsnes and Våler municipalities in Hedmark during the period Karl describes show that his story is not unique. At the time, there were fierce debates in local newspapers about what to do about the "Tater problem."

- 1/2

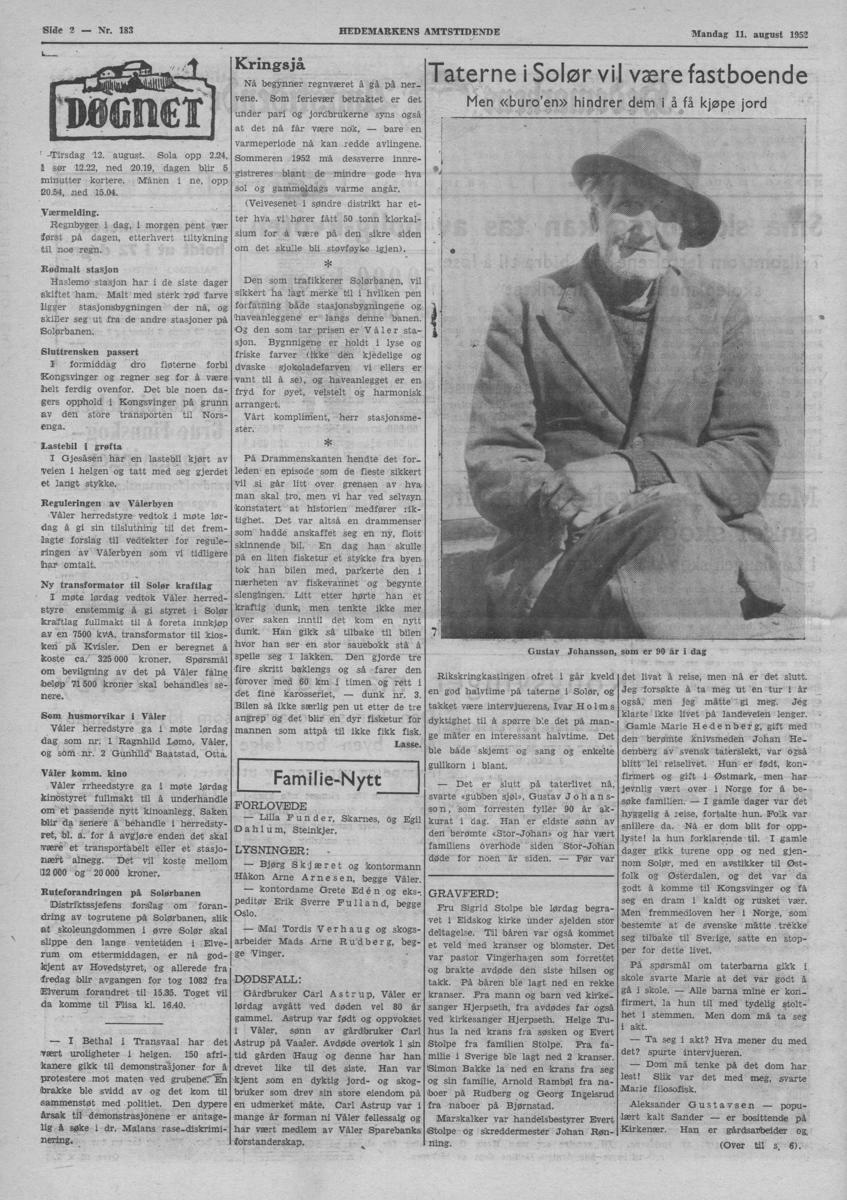

The Travelers in Solør want to settle down. Newspaper Hedmarkens amtstidene 11 Aug. 1952. Nasjonalbiblioteket - 2/2

Has Våler in Solør become Hedemarken’s Little Rock? Newspaper Stiftstidene 6 Nov. 1963. Nasjonalbiblioteket

Methods used to prevent the tater people to settle

There were three methods the municipalities frequently used to prevent people of Traveller heritage from settling in their municipality. The first was to keep a tight rein on the concession rules that were implemented during World War II. These rules were intended to regulate agriculture and were not intended to apply to regular land sales. By introducing a low concession limit (or by introducing concessions on all plots), the municipalities gained control over the sale of all properties, both those owned by the municipality and those that were privately owned.

The municipality could also control who could buy a house or a plot. In this way, they could also regulate how many of Tater people had the opportunity to get their own residence.

A third method was the introduction of a municipal pre-emptive right. This gave the municipality the right to purchase houses that were either owned or rented by a Tater family or were in danger of being bought or rented by families of Tater heritage, thus preventing such purchases and rentals (Møystad 2015).

Through these methods, municipalities often managed to prevent people of Tater heritage from settling in their jurisdiction. Many newspapers in the 1950s and 1960s pointed out that: "[E]veryone wants the Tater people to settle down, but no one wants them as neighbours!" Despite the authorities' diligent efforts to prevent them from settling, they did not give up so easily. Many applied for a plot year after year. As Karl’s story shows, they could buy land from third parties; some changed their names so that no one would trace their heritage; yet others showed up at local council meetings to speak up. The Tater people’s struggle to settle is just one of many stories from their tenacious battles to be accepted in Norwegian communities (Møystad 2008, 2015 og 2016).

- 1/1

Applying to purchase land to settle down, a time travel at the Glomdal Museum in 2017. Foto: Anno Glomdalsmuseet.