- 1/2

Woman's clothing from the exhibition. Foto: Anno Glomdalsmuseet - 2/2

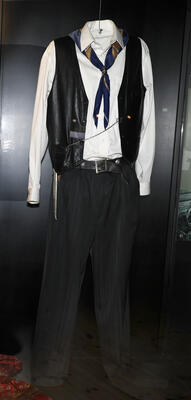

Man's clothing, from the exhibition. Foto: Anno Glomdalsmuseet

Women’s clothing

A married woman always wore a diklo on her head - a headscarf tied in a special way. Owning lots of jewellery was a sign of prosperity and status. The women usually wore many gold rings in different shapes and widths but the gold solder ring a woman got from her fiancé was the finest. The solder ring would normally weigh at least 30 grams.

- 1/1

Wedding rings, man's pledge ring and woman's solder ring, and ear ornaments in gold. Foto: Anno Glomdalsmuseet

On their chests, the women wore filigree brooches and pins. These filigree brooches were intended to be large, with the largest being up to 15-20 centimetres in diameter. The women's belts were made of leather and cloth and had large buckles.

- 1/3

Embellished belt. Foto: Anno Glomdalsmuseet - 2/3

Filigree brooch by Johan Julius Johansen. Foto: Anno Glomdalsmuseet - 3/3

Heartshaped belt buckle in brass, with engraving. Foto: Anno Glomdalsmuseet

- 1/3

Marie Lovinie Oliversen, Big-Johan’s daughter, dressed up in her «Queen’s outfit», 1974. Foto: Lasse Torseth - 2/3

Personal jewelry: comb, filigree brooch and belt buckle. Foto: Anno Glomdalsmuseet - 3/3

Jenny Emilie Pedersen, «Milla», wearing her diklo and brooch, ca 1973. Foto: Anno Glomdalsmuseet

A Tater woman usually wore several layers of skirts, and she wore her porshika (loose pocket) under one of them. This was where she kept money, valuables, her smoking pipe and tobacco. The pipe, according to Marie Lovinie Oliversen, was supposed to be a genuine Lillehammer pipe, preferably with a lid. This made it a real "women's pipe". “The Tater women had lids on their pipes so no embers would fall on their babies when they nursed”, says Milla.

- 1/1

Lidded woman's pipe. Foto: Anno Glomdalsmuseet

The Tater people who were young in the 1950s and 1960s were the first ones to stop wearing the traditional clothing, but even now many older Tater women still dress in the traditional way. It is also becoming increasingly common, especially among those who have not grown up with a life on the road, to show their identity and heritage by dressing up in traditional clothes on special occasions.

Men’s clothing

A man’s outfit commonly consisted of a wide-brimmed hat or six-pence cap, a colourful scarf fastened with a large ring, and a shirt or vest. The vest was often made of leather, with silver buttons. A pocket watch on a silver watch chain hung from the vest, and there was a leather wallet in the trouser pocket. In addition, the outfit included a jacket and trousers that were held up by a studded belt.

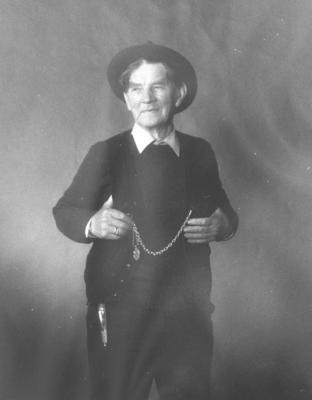

- 1/5

Elias Rosenborg with knife, pocket watch chain and hat. Foto: Anno Glomdalsmuseet - 2/5

Pocket watches in gold, with engraving. Foto: Anno Glomdalsmuseet - 3/5

Pocket watches in gold. Foto: Anno Glomdalsmuseet - 4/5

Man's wedding ring. Foto: Anno Glomdalsmuseet - 5/5

Pocket watch and chain. Foto: Anno Glomdalsmuseet

The knife, which was often a simple Mora knife, was attached to the belt or lay in a loose sheath in the pocket. They usually wore tall boots on their feet (Schluter 1993).

The men often wore rings too. The pledge ring was a very wide gold ring that could be used as a pledge if a man did not have enough cash while trading. It could also be pledged against goods or cash.

Romani bunad

It is now possible for the Tater people to express their identity through their own costume, or bunad.

Peggy Enerud, who is known as a Christian singer, and Mariann Grønnerud, a consultant at Anno Glomdal Museum, have designed the Tater bunad. Anno Glomdal Museum has contributed to the project, which is supported through a grant administered by the Arts Council of Norway, with the title “The collective reparation for the Tater/Romani people”.

It was important to Peggy and Mariann that the bunad be expressive of identity and reflect a proud people who have faced many hardships.

The women’s bunad was ready in 2021, and the men’s bunad the following year. The design process was aided by photos from the Anno Glomdal Museum archives, and the Norwegian Institute for National Dresses has provided advice.

- 1/3

Mariann Grønnerud wearing the green women's bunad. Foto: Ricardo foto - 2/3

Peggy Enerud wearing the red women's bunad. Foto: Ricardo foto - 3/3

David Kirkenes wearing the men's bunad. Foto: Ricardo foto

The bunads are not “reconstructed”. As there are few Tater garments left, photos were utilised in the search for insight into the characteristic way of dressing that the Tater people had.

The women’s bunad has patterns and brooches rich in symbolism, which is typical of the Tater style. The blouse is adorned with roses, cuffs are in the shape of cartwheels, and there are woven birds at the waist, while the collar brooch symbolises hope, faith, and love. At the hem of the skirt are embroidered notes from the song Se min ild, “See my fire”.

As opposed to other Norwegian dresses from a specific place or region, this bunad is made for a people with connections to different places throughout Norway.

- 1/3

Women's brooch, the ship's wheel. Foto: Sigmund Espeland - 2/3

Golden ring for the men's scarf, decorated with a rose. Foto: Sigmund Espeland - 3/3

The back of golden pocket watch for the men's bunad. Faith, hope and love. Foto: Sigmund Espeland

- 1/2

Large women's brooch, cart wheel. Foto: Sigmund Espeland - 2/2

Chain for watch. Foto: Privat/Anno Glomdalsmuseet