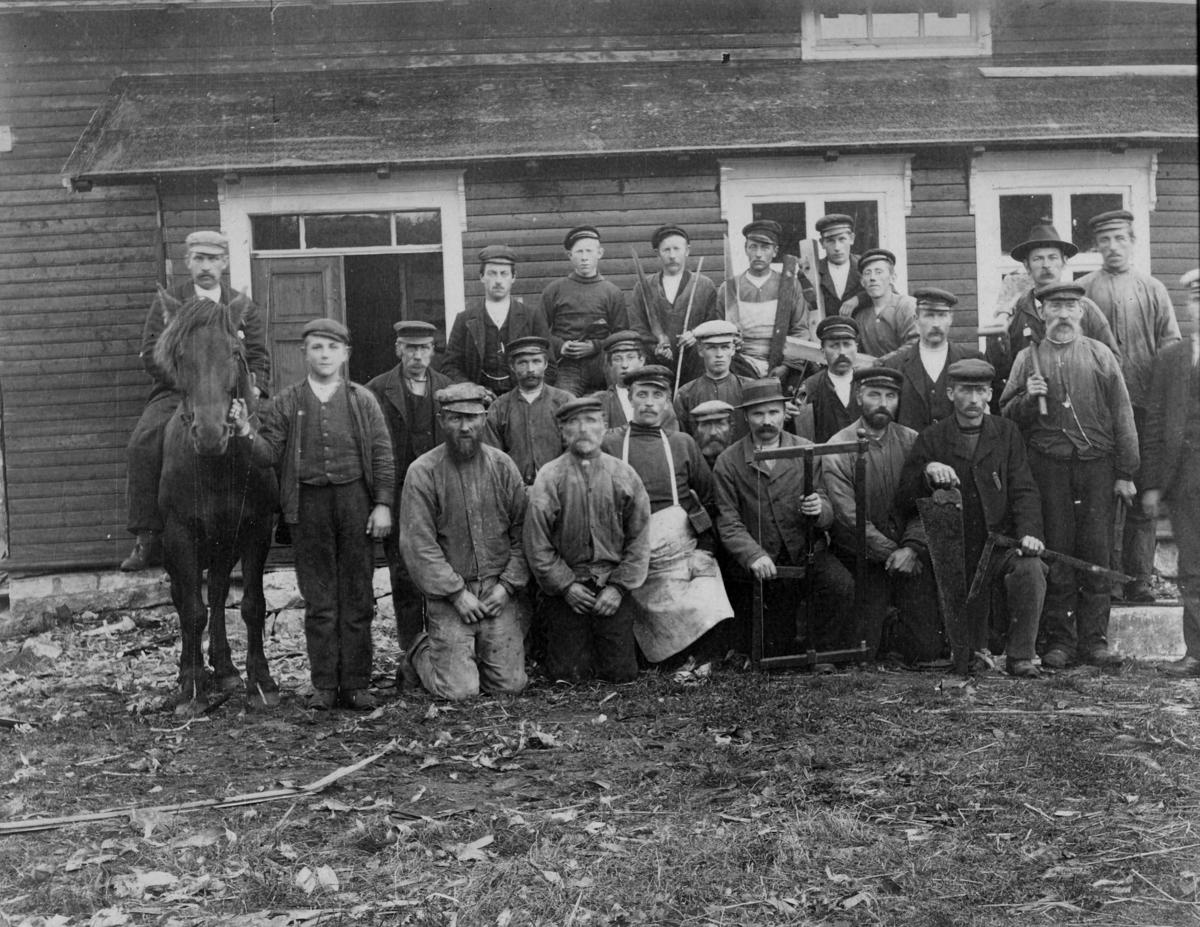

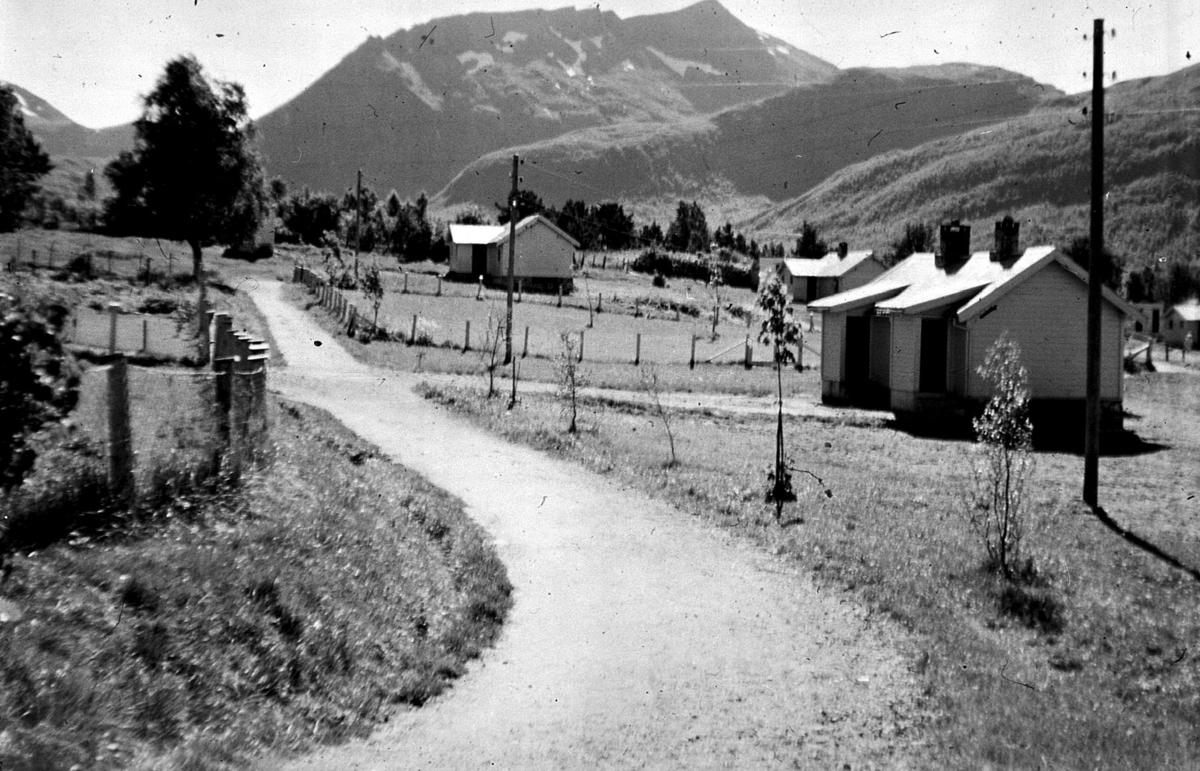

Svanviken work camp and Bergfløtt work camp for single men

To implement the settlement project, the Mission wanted to set up three work camps for families and one for single men. Due to lack of funding, only two were established: Svanviken work camp for families, established in 1907, and Bergfløtt work camp for single men, established in 1911.

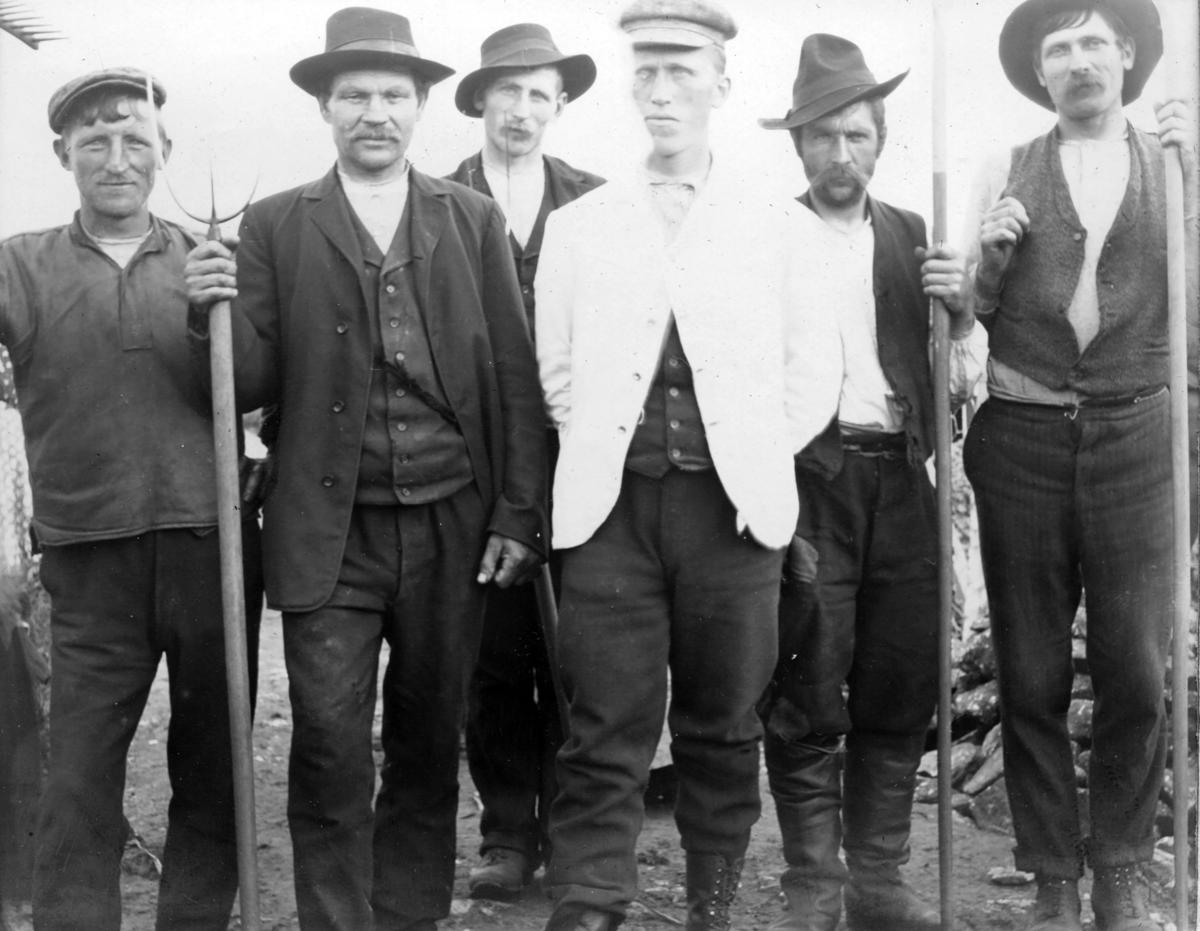

The settlement process was based on a period of trial and learning, where the “vagrants” got accustomed to a calm lifestyle and regular work (Møystad 2015 and 2016).

- 1/1

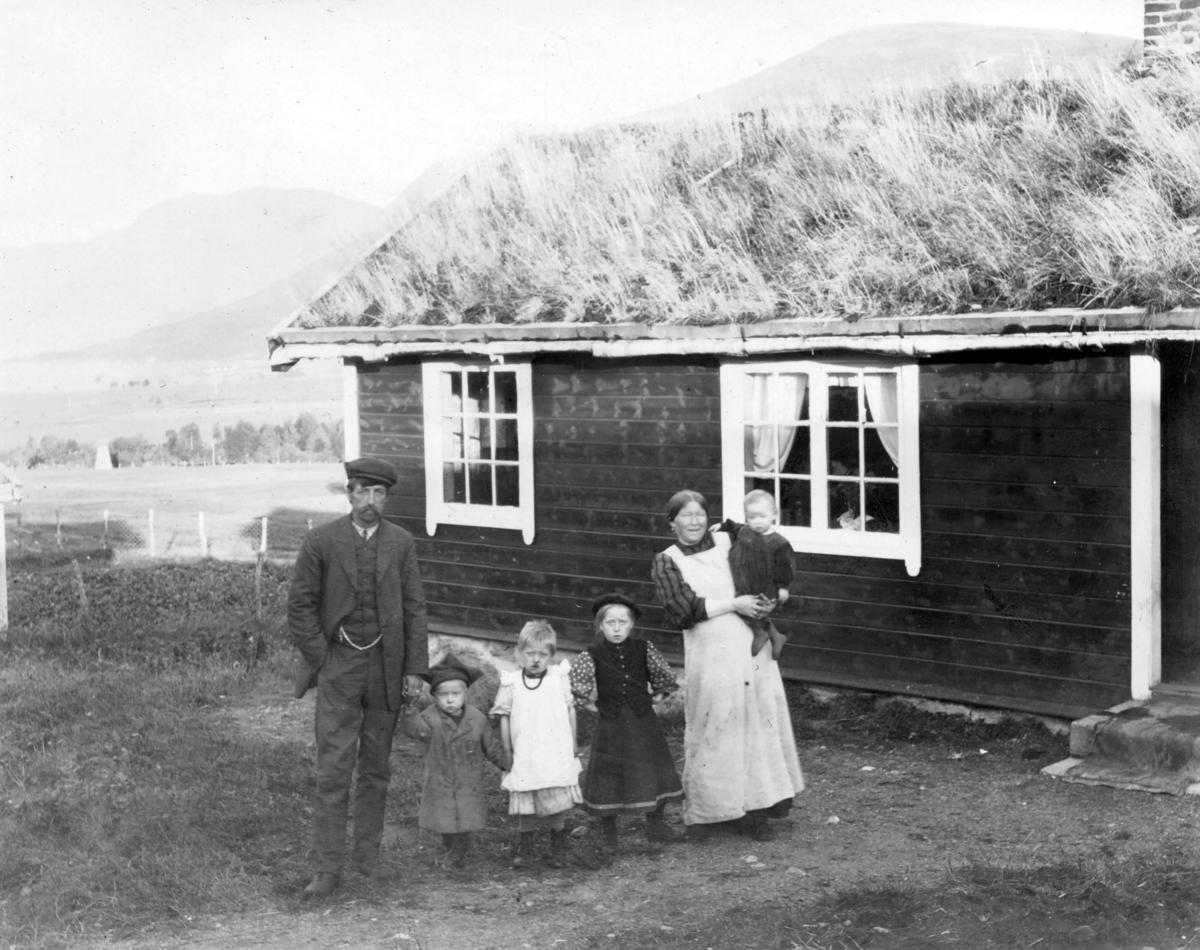

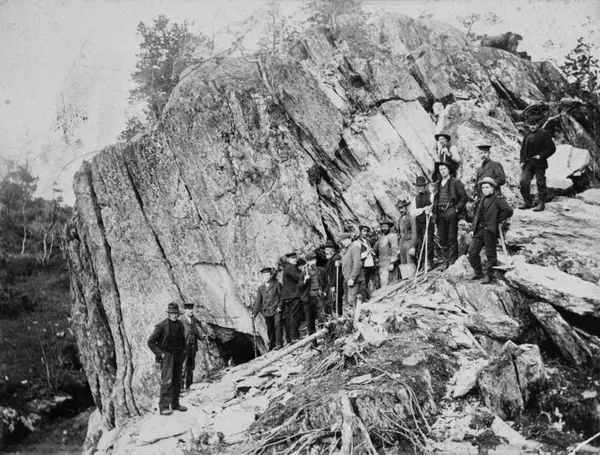

Familie på Svaniken, ca 1914. Foto: Anno Glomdalsmuseet