Since the late 1880s, their traditional professions have been linked to horse-handling, crafts and sales. Like other Norwegians, today’s Romani people have many different professions, but many still earn their living from trading and crafts, and a successful act of trading is still highly appreciated.

The Romani people’s chosen professions have been characterised by continuity and adaptation: continuity with regards to tools and raw materials, and adaptation in relation to changing market needs (Moe 1975).

- 1/1

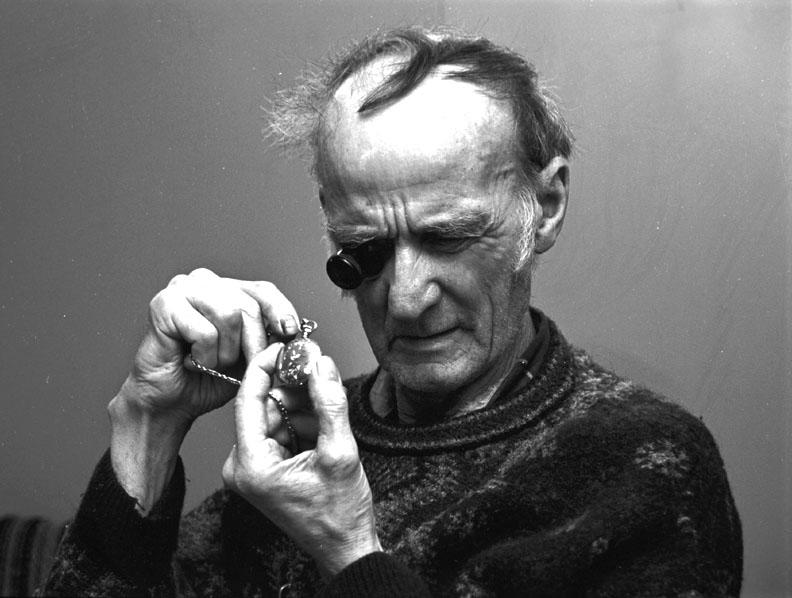

Selling from farm to farm. Foto: Toten Økomuseum

Despite the fact that increasing industrialisation and centralisation made the Romani people’s businesses more vulnerable, they were good at adapting to changing market needs.

Nevertheless, the range of occupations which formed their livelihood has declined over the past fifty years. By the beginning of the twentieth century, the Romani people had already lost many of their previous professions. In the Fantefortegnelse 1845 (the 1845 vagabond list), many professions are mentioned that disappeared over time due to dwindling markets and increased industrialisation. The vagabond list shows, for example, that many men were involved in metal work and in the handling of horses, raddle binding and sweeping chimneys. The latter two professions disappeared in the second half of the twentieth century.

The professions that disappeared

Raddle binding was common in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In the first part of the twentieth century, raddles started to be mass produced in the weaving mills, and the Romani people lost this market. Other professions, such as chimney sweeping, were taken over by residents. A military career, which had been popular for many years, disappeared due to professionalisation.

Some of the former professions for Traveller groups in Norway were associated with notions of unclean or dishonest work, such as working as an executioner, slaughtering, chimney sweeping and refuse work (Moe 1975).

Those who did the “unclean” work were called rakkere (“villains”) or nattmenn (“night men”). In Denmark-Norway, the hygiene regulations were very strict in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. For example, farmers were not allowed to spread manure on their own farms. This was a service provided by the unclean. Prejudice against different types of unclean work disappeared during the nineteenth century, and so did much of the market for this type of work (Moe 1975).