The guardian act

A law aimed at protecting neglected children, later known as the Guardian Act, was approved by the Storting in 1896 and entered into force in the year 1900.

The Act contained provisions that permitted public authorities to act if parents were perceived as neglecting their children. The children could then be placed in foster homes or orphanages.

The first paragraph of the Act defined three criteria for handing down a guardian resolution for removing the child from its home:

1) that the child had committed a crime; 2) that the child’s behaviour was such that he was in danger of becoming a criminal; and 3) that the child had no provider or that his living conditions were so poor that he had become, or was in danger of becoming, depraved.

The last criterion was the one most frequently used with Romani families. The reason given for the removal of Romani children from their families was often that the travelling life was harmful to the children (Official Norwegian Report 2015:7).

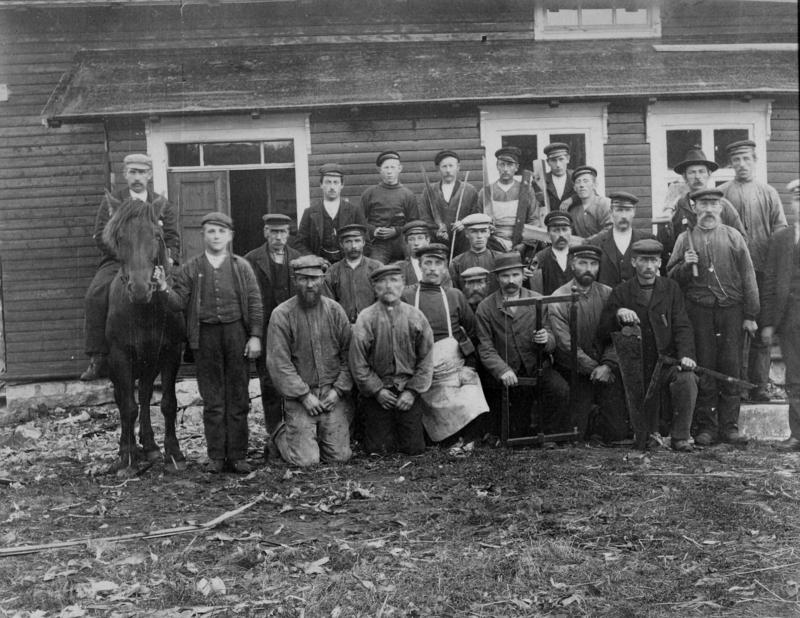

- 1/1

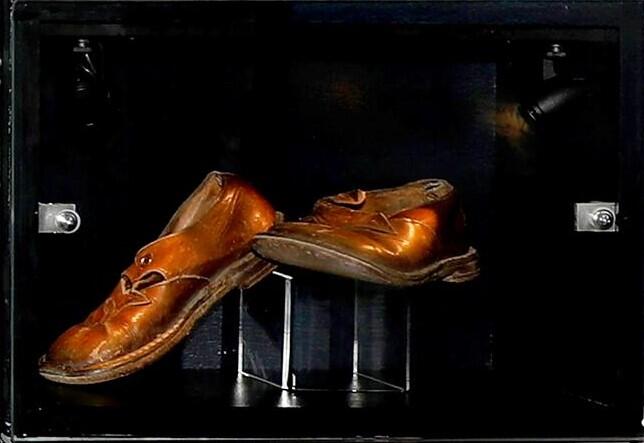

Fotograph of shoes from the exhibition at Glomdal Museum. Foto: Anno Glomdalsmuseet

The vagrant act

This law made it lawful for the Mission, acting on behalf of the state, to force “vagabonds” to settle down, with or without their consent.

This Act was passed in 1900 but entered into force in 1907. Under Section 7 of the Act, a vagrant was understood to be someone who “[…] indulges in idleness or roams about, stays outside his residence and does not on request […] satisfactorily explain his sources of income – or who – upon release from jail for vagrancy, cannot prove the existence of a permanent residence”.

It was further stated that, “… if he cannot or will not obtain a permanent residence, he is obliged to accept a residence assigned to him according to the rules laid down by the King.” According to the Act, the police were to “persuade him to obtain such residence and, if possible, assist him in doing so.”

The detailed rules were provided in a resolution dated 27th November 1907, which stated, inter alia, that the Ministry of Church and Education was responsible for forced settlement and that the Mission carried it out.

- 1/1

Handcuffs from the exhibition. Foto: Anno Glomdalsmuseet

The trading act

The Trading Act was first passed in July of 1907, then revised in 1929 and again in 1935. It regulated “peddling”: that is, sales taking place without a permanent sales outlet. This kind of trade was primarily carried out by Jews and Romani people and had not been regulated previously. With this new law, peddling became unlawful without police authorisation, and travelling around to sell goods required a trade licence.

The law also established that people suspected of being beggars or vagabonds should not be granted trade licenses in order to carry out such peddling.

There was also a warning against such trade, which was said to be detrimental to the pedlar because it resulted in a migratory lifestyle and “moral decay”.

- 1/1

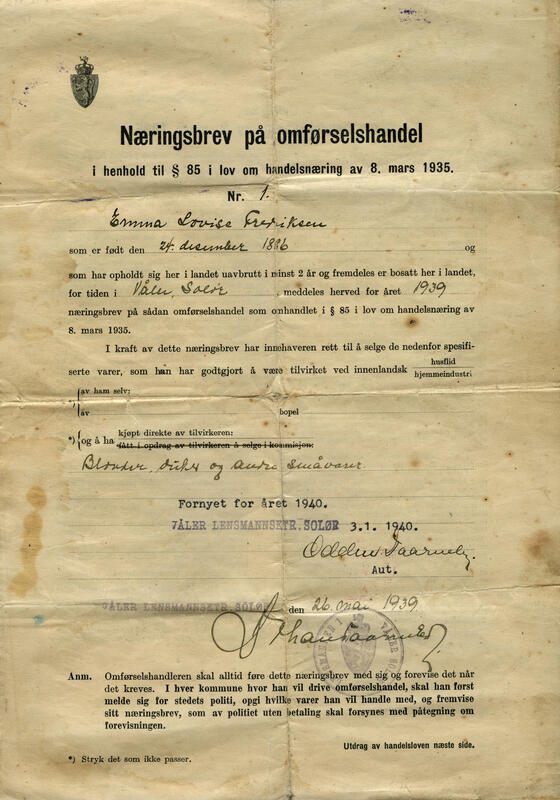

Trade license. Foto: Anno Glomdalsmuseet

The sterilisation act

During the latter half of the 1920s, new research emphasised heritage more than environment. Advocates for this view placed importance on the prevention of racial mixing and the prevention of individuals with poor genetic qualities from being able to multiply.

The Sterilisation Act of 1934 marked the end of a long debate regarding racial hygiene. It was modeled on the German Sterilisation Act and permitted forced sterilisation of the retarded and mentally ill, as well as sexual offenders.

From 1934 to 1977, 128 Traveller family members were sterilised under this law, and 40% of the women at Svanviken were sterilised. How many were sterilised outside of this provision is unknown, but there is reason to believe the number of unrecorded cases is significant (Haave 2000).

The travellers were looked upon as a people who had poor genetic qualities. This is quite clear from the drafting of the law, which stated the following:

"They (the travellers) belong to a lower-class people recruited from the scraps of society. Intellectually, the Norwegian travellers are at the same level as Negroes, Indians and Mexicans. Socially and psychologically, they should be placed along with habitual criminals."

- 1/1

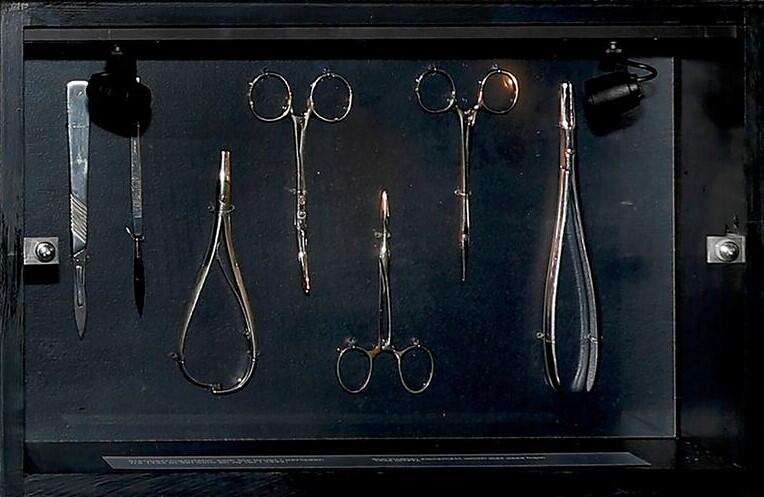

Tools for sterilisation from the exhibition. Foto: Anno Glomdalsmuseet

The animal protection act

In 1951, a new paragraph in the Animal Protection Act stated that “vagabonds” could not use horses while travelling from town to town to trade.

§10, section 14 of the law stated: “It is illegal for vagabonds, when they move around, to use horses or other animals to carry people or goods, or to have loose horses with them.”

The official reason for introducing this paragraph was to protect the animals, but the real goal was to force the Romani people to give up their nomadic lifestyle. This became apparent when the paragraph was abolished in 1974, with the following justification: “The kind of lifestyle the rule applies to is no longer common, so the ban is no longer very relevant.”

- 1/1

Horse shoe from the exhibition. Foto: Anno Glomdalsmuseet

Karl explains the animal protection act

- 1/1