The mission’s work

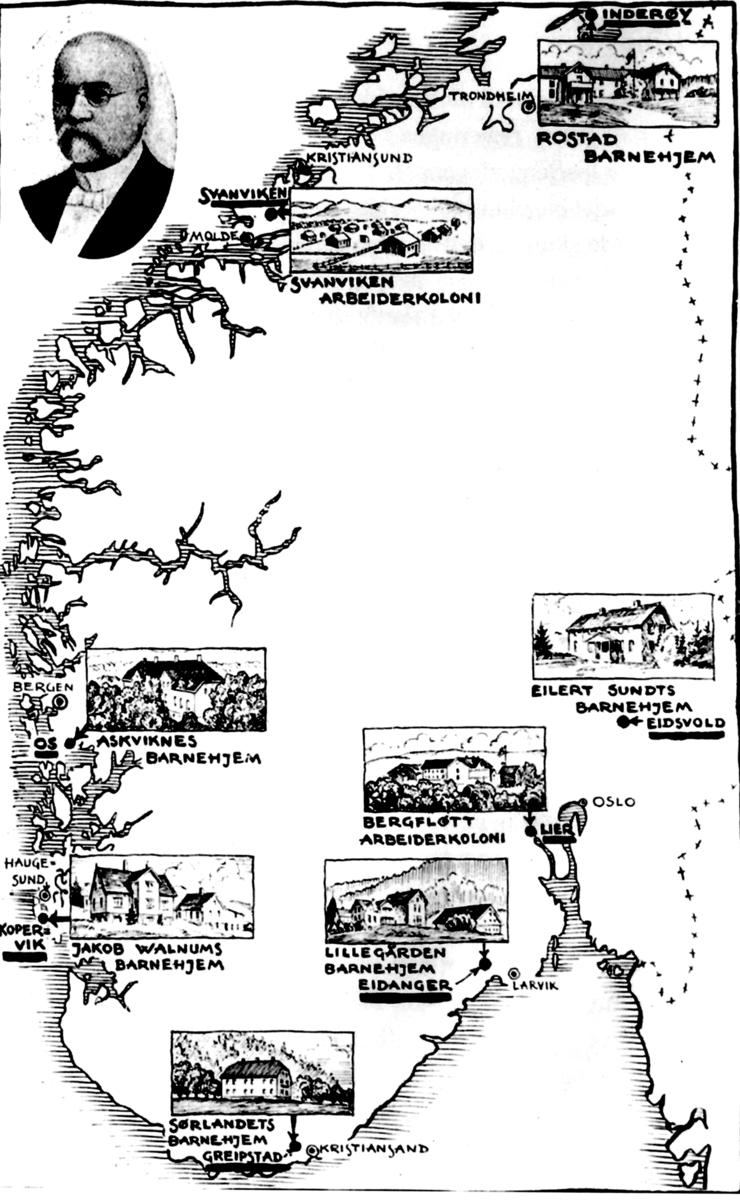

From the start, the Mission had two aspirations: one was the work related to children, which consisted of removing children from their families and placing them in orphanages or foster homes; the other was to make individuals and families stop their travelling life and settle down. In both cases, cultural assimilation was the goal.

While the Guardian Act of 1896 gave the authorities permission to carry out their “child rescue operation”, the Vagrant Act of 1900 was the basis for the establishment of settlements. Through these two acts, the Mission and the authorities aimed to destroy the “vagrant evil”.

- 1/1

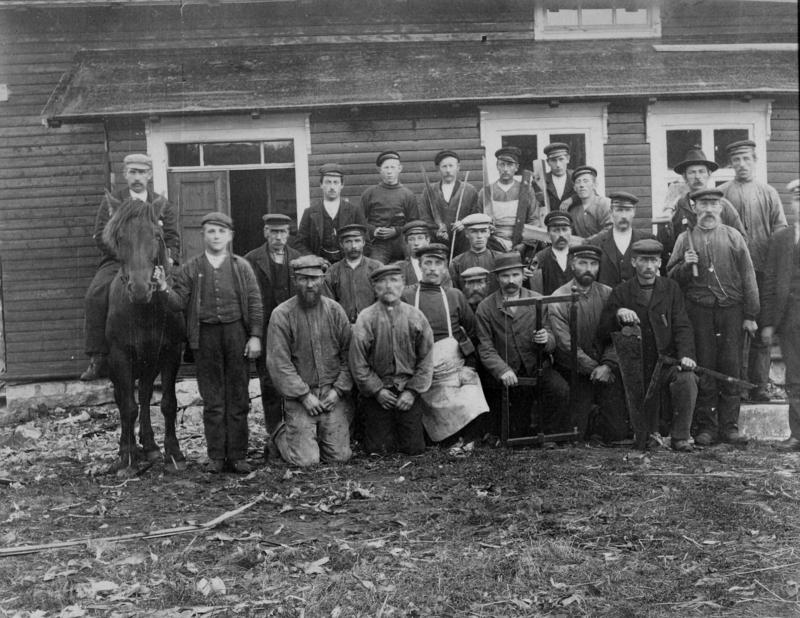

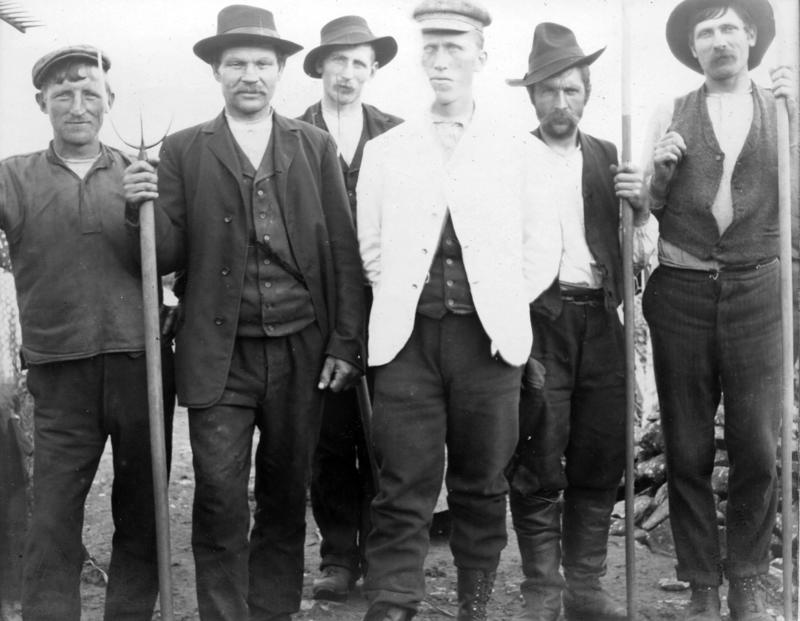

Ploughing, two men with horses and plough, Svanviken work camp. Photo: Norwegian Mission for the Homeless’ archives, National Archives of Norway, Anno Glomdal Museum. Foto: Arkivet til Norsk Misjon blant hjemløse / Riksarkivet

Strictness and gentleness

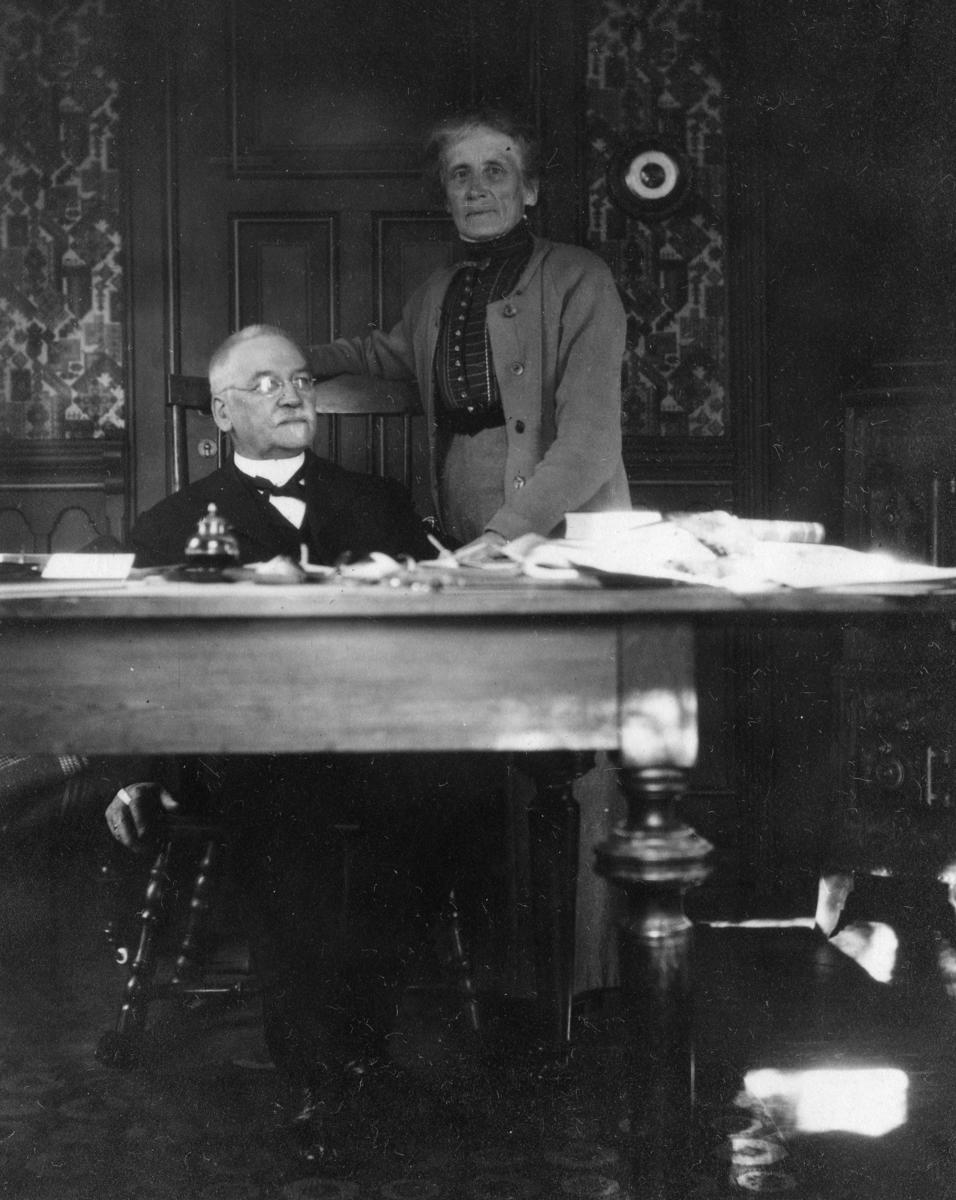

Walnum stated that Eilert Sundt’s work failed because he lacked a formalised plan, and because the government had not granted any power to carry it out.

Walnum felt that the interaction between the Mission’s volunteer work and the authorities’ enforcement was the key to the work: “Strictness and gentleness must go hand in hand”, argued Walnum. “The state represents force, the association gentleness. A good result is dependent on both working together and supplementing each other.”

The authorities made and enforced several laws that criminalised a travelling lifestyle. The Mission was given the responsibility for implementing different social welfare measures towards the group, and the authorities funded this work. This division of labour lasted until the end of the 1980s and prompted researchers, Bjørn Hvinden among others, to call the Mission “The directorate for the Romani people”.

- 1/1

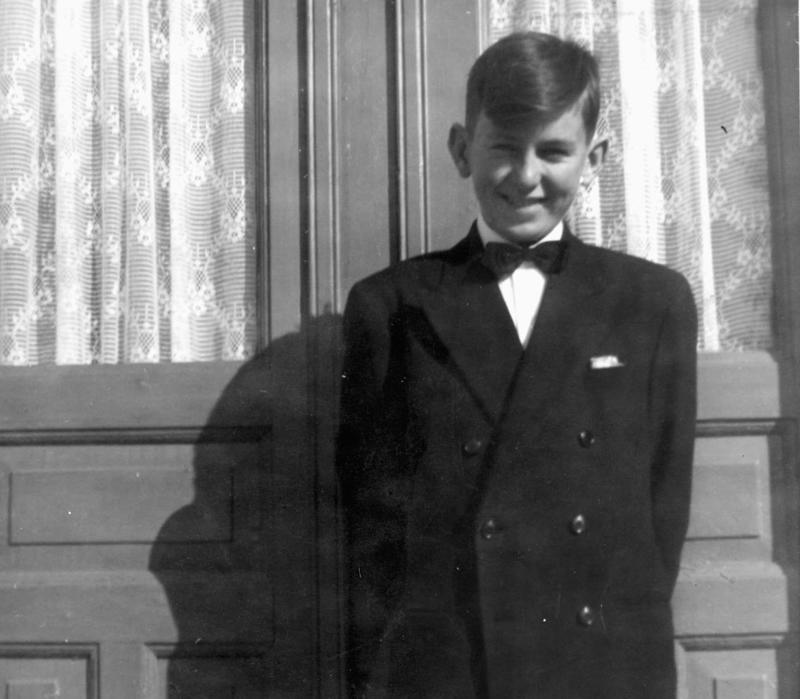

Orphanage children lined up, ca. 1914. Foto: Jacob Walnums samling / Anno Glomdalsmuseet