Horse handling and trade

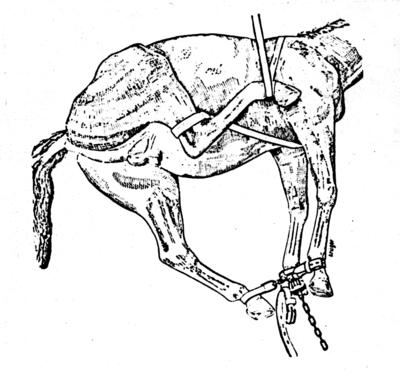

The vagabond register for the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries shows that many Tater people were registered as gelders: they made their living castrating horses. Castrating a stallion was done by blocking the production of hormones in the testicles. This was most easily done by cutting the sperm ducts with a knife. To prevent potentially fatal bleeding, wooden clamps were placed on the sperm ducts and blood vessels, then the sperm ducts were severed. The wooden clamps were treated with a blue vitriol ointment to prevent infection. The clamps remained on the horse for a couple of weeks. Another method was to place the clamps across the sperm ducts, blocking circulation, which killed the tissue (Moe 1975).

- 1/2

The horse is laid on its side and tied up with chains and long straps. Drawing: Tore Lande Moe, 1975. Tegning: Tore Lande Moe - 2/2

Castration with wooden clamps without opening the scrotum. Drawing: Tore Lande Moe Tegning: Tore Lande Moe, 1975.

The Tater people made all the equipment they needed: knives, clamps and ointment. A migratory lifestyle was an advantage for this activity because one could reach a large area. In the same era, many Travellers were also registered as gelders to various regiments; others were enlisted as soldiers. Many were good at healing animals. The knowledge was passed from father to son. Others were skilled farriers and could set up an improvised forge if a farmer needed horseshoes or horseshoe nails for the horse.

Market trading and trading with horses

Horse-trading was a natural business for the Tater people who had a lot of knowledge of this animal. It was usually carried out at the markets, but also on farms and posting stations. They were colourful fixtures at local markets around the country and this was where they usually traded horses and watches. The trading took place in eastern Norway and at venues such as the Stav Market at Tretten in Gudbrandsdalen, the Grundset Market in Elverum, the market in Lillehammer, Dyrsku'n in Seljord, the Romsdal Market at Veblundsnes in Åndalsnes and the markets in Trondheim and Levanger.

The markets were also meeting places for knife-trading. Trading in tin work also occurred, and if there was ever work the Tater/Romani people knew well, it was tin work. Bartering was also common.

Horse-trading was profitable, and "Big-Johan", who was known as the first ancestor of one of the largest and most respected Tater families in eastern Norway, did a lot of it. Marie Lovinie Oliversen, one of his daughters, says this about his horse-trading: "First and foremost, we lived off horse-trading. That was the main source of income". Big-Johan was a popular horse-trader: "When he brought his horses, the farmers knew they got decent wares", says Milla, another of Big-Johan’s daughters (Grønoset 1974).

One of Big-Johan’s grandchildren, Aleksander Gustavsen, who traded horses all his life, said in an interview: “We were never mean to the horses, but we bought skinny and poor horses and let them graze along the roadside, then we sold them.” Even though the Tater people treated the horses well, a law was passed in 1951 that deprived them of the right to keep horses when they went on their trading trips. Once this law was passed, much of the horse-trading at the markets stopped. But watches are still being sold at the Seljord market, and at the Grundset Market in Elverum you can still buy a genuine "Tater knife".

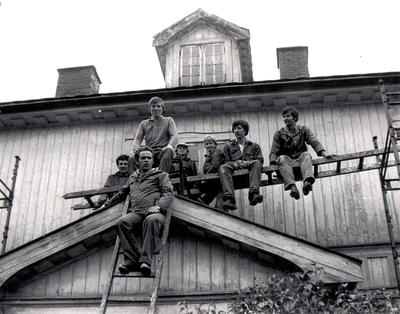

- 1/1

Watch trading

The Tater people repaired, engraved and traded pocket watches. They repaired watches in the villages and swapped and sold them in the markets. They were clever at trading and knew many tricks that could keep the watches working, at least until the transaction was completed.

Milla remembers the Grundset Market in Elverum in the early 1900s as a place where: "People from Gudbrandsdalen brought stockfish and salted herring; people from Toten came with tin ware and copper; Swedes with iron, nails and Mora knives, and the Tater people rushed there to start horse-trading and watch swapping".

Watch-trading was also done as peddling, but the biggest turnover was accomplished at markets where a lot of people were gathered. Watches were most often swapped. The person who had the watch of lesser value paid the difference.

- 1/1

Watch repair. Foto: Levanger Museum

This article in Hamar Stiftiendende (local newspaper) on May 6, 1959, titled Klokkebytterne (“The watch swappers”) describes how a watch swap might take place:

“If you give me 20 kroner and your watch, you'll get this one”, says a Tater from Kirkenær. This is a nice watch, I can tell you. You can have 10 kroner to make up the difference. “No, I'm not giving away my watch for one that's cheaper for only 10 kroner”, another man responds, “I’m not that dumb, but okay, let's say 15 kroner...” “How many do you want?” He pulls out eight watches: pocket watches, ladies’ and gentlemen’s wristwatches in the strangest sizes and varieties. And they aren’t in a bag - what's the use of that? No, they are in trouser pockets, jacket pockets, inside pockets and watch pockets, and then he has one on each wrist.

- 1/1

A selection of pocket watches. Foto: Anno Glomdalsmuseet

Scrap business

The Tater people used their knowledge of metals to become scrap dealers. They collected used metals, purchased various junk and sold it to companies and factories in the cities.

- 1/1

Gutter work. Karl Magnus Karlsen and his two sons out on a job, ca. 1950. Foto: Privat / Anno Glomdalsmuseet.

Metal/tin work

Casting

Tater were also braziers: that is to say, they cast metal. They made buttons, belt buckles, combs, hooks, parts of harnesses, and bells. The only items of equipment needed for this work were a crucible, moulds, metals and a furnace.

Blacksmiths

Tater also specialised in making silver and nickel silver products. Nickel silver is a copper/nickel/zinc alloy. Nickel silver is similar to silver but is more affordable and easier to work with.

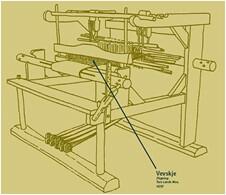

Tin working

From the latter half of the 1880s and into the twentieth century, tinwork was a common craft among the Tater people. The tools needed were simple: tin scissors, a wooden club and a soldering iron. The materials – tin plates – were cheap to purchase and easy to transport. The products they made were kitchen utensils such as bread and cake moulds, bread bins, ladles, funnels, tubs, buckets and troughs, milk strainers and milk pails, dustpans and paraffin cans. The Tater people were inventors within this field, and many new products were created. For example, the spring-form cake tin was invented by a man of Tater heritage.

When tin went out of style as the material used for kitchen utensils, many Travellers switched to the production and installation of gutters. Then industrial gutters came onto the market in the 1970s and 1980s. In recent years, the sale of fire escape ladders has been a supplement to gutter work.

Tin coating and pot repair

Tin coating and pot repairs were secure sources of income for the Travellers. Copper household products had to be tin coated (covered with tin inside). Direct contact between food products and copper could lead to deadly poisoning. As the tin cover became worn, it had to be renewed. When copper cookware was replaced by new materials, this business dried up.

- 1/3

Wire craft. Foto: Anno Glomdalsmuseet - 2/3

Chest clad with copper relief. Karl Nikolaisen. Foto: Anno Glomdalsmuseet | - 3/3

Working men. 1983. Roa. Foto: Privat / Anno Glomdalsmuseet