Childhood

"I grew up with three older brothers – an ‘afterthought’ – and probably a little spoiled, but in a positive way. I was 12 years younger than my youngest brother. Their upbringing was practically finished when I came along.

We all lived in a house for the most part. It was not a big one. There was only a living room, a kitchen and one bedroom. Two of my brothers lived at home, while a third had already moved out when I was born. When I was between the ages of 10 and 12, my remaining brothers moved out.

My sisters-in-law washed floors and cooked. We helped each other. It was normal at that time for many people to live together, so I didn't think much about that. I remember that sometimes, when I got home a little late, my bed was occupied, and I just had to find somewhere else to sleep. One of my brothers had two kids who also lived with us. And sometimes unexpected guests came to stay. No one was ever rejected. As long as there was room on the floor, then there was room to sleep. The saying goes that where there is room in the heart there is room in the house, and this was true in our case.

My parents worked in trading and sold everything from bobbins to gutters. They also traded antiques. My brothers were both tinsmiths and antique dealers. They worked with Dad and by themselves. They each had a truck with a mobile workshop, where they had all kinds of tools.

I had few duties at home and probably got away with that until I was 14 years old. Then Mum got sick, and I had to take over as the housewife and learn how to wash clothes and cook. I remember burning the sausages. My Mum died when I was 16, so then I had to stand on my own two feet. My brothers no longer lived at home.

We moved a lot when I was a kid. I was born at Dal. When I was 8 years old, my dad sold the house in Dal and bought one in Trøgstad. When I was 10, we moved to Bø in Telemark, and thereafter we moved to Sweden.

My father also once bought a plot in Elverum, but we never lived there. We lived for a period in Våler after returning from Sweden. When I was 14, we moved to Kjellmyra. By then, my mother was already sick. At first, they didn't know what was wrong with her, but they eventually discovered she had cancer. After she died, I got a job at the Globe Factory. I didn't like that job. It was monotonous and boring. Everything happened according to a schedule. It didn't suit me.

During my childhood, I spent a lot of time with my grandparents on my father's side. They had horses. My mother's parents died early. We saw our cousins often, many times a week, visiting each other.

I had a close relationship with my parents. In many ways, I was probably a tomboy. I went on fishing trips with my father and my brothers. I guess I took part in just about everything and my dad always took me along.

My mother taught me how to cook. Although both my parents were of Tater heritage, they were used to having their own house.

My father was from Furua and my mother came from Trøndelag. They lived in Stjørdalen for 23 years before they moved south. They wanted to try something new. I remember my childhood summers the best – the trips to western and southern Norway. We were often in the mountains, trading with people on the summer farms. My father traded cod liver oil for trousers, which he then sold. I remember quite often being awakened by my father serving trout with sour cream. He used both natural and sweetened sour cream. I liked the sweet one the best. He got up early to go fishing before I woke up. Father also made "coal buns" - thick pancakes with pork inside. It's really lumberjack food, but we loved it. My mother didn’t mind that he cooked as well. Usually, she provided all the meals.

When it came to games, I remember jumping and bouncing a lot. We did forward springs, played football, tipped sticks, and chopped pogo sticks. If there were several of us, we played dodgeball. These were our everyday games. We played with other kids or with the adults.

In Våler, I remember having a friend at one of the farms. We were a little afraid of the residents, or I guess we were afraid of each other. There was definitely a natural separation. We were different and people are afraid of anything that is different. The villagers were also different, so why would they come to a house full of Tater? We were also very loud and that was probably a little scary.

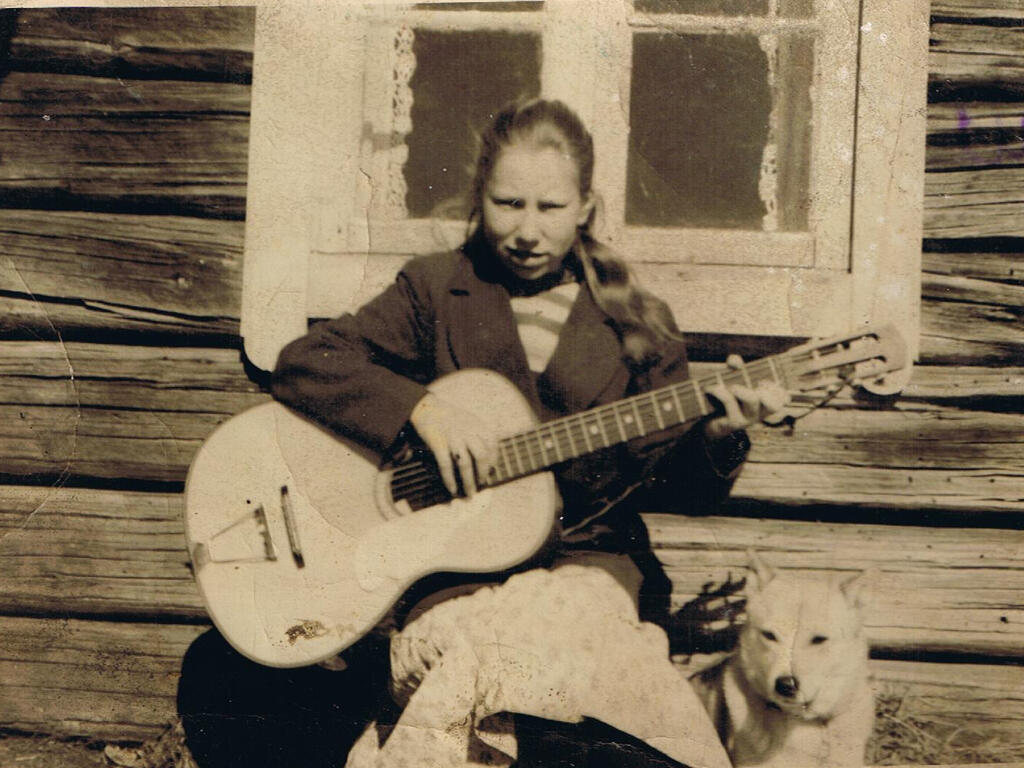

There were also people in the villages who were friendly and not prejudiced. My friend came from a home like that. We met on our way to school since we lived close to each other. I was very fond of singing and playing. In the evenings, I often brought my guitar to the stairs outside and sang. She would come out to listen. I was very proud then because I had an audience.

Despite the difficulties and poverty, I had a good childhood. We had a lot of anxiety because of the authorities looking to take their children from the Tater people. During the worst period, I was often left on a farm when my parents left to sell antiques. I might stay on the farm for 2-3 weeks. I had my own room there and remember that the farmer’s wife had canned meatballs and that she baked delicious white bread. Even so, it broke my heart to see my parents leave. I was very sad and had a lump in my throat. I felt very hurt. Blood is thicker than water. My parents said it wasn't good to have kids along on the road. If someone had seen them travelling with a child, they would have taken the child.

My niece was taken by the Mission when she was four and was living with her mother and stepfather in a tent. I was 12 years old then. The Mission came and picked her up. We sent her care packages. She got the packages, but she never found out who they were from. Once, when I got a doll, we sent it to her. She did not do well after the Mission took her. We were looking for her and knew where she was. My mother was in contact with the manager at the orphanage to try to get her back, but it did not work. We did not see her again until she was 40 years old.

As Tater we were at the very bottom of the social ladder, but we tried to fight our way up. We've been minding our own business and we haven't learned to stand up for ourselves. There were special laws for us. Therefore, it was important to be invisible. Now that the special laws are gone, we have security and can take a stand. We're also entitled to certain things."

Schooling

"We did not always get the right education. I guess it was due to many circumstances: our culture, life on the road and people's attitudes. The schools were not very interested in our education. The attitude was that nothing would become of us anyway, so it wasn't important. If we went on the road, the school had one less problem.

For us, school was not a good place to be. I've taught myself to read and write! Altogether, I have no more than two years of school. I went to school for a few winter months in Dal, a little in Trøgstad, a couple of months in Sweden and a few months in Våler.

Våler was the only place where I had a friend. In the other places I went to school, I stood mostly by myself. I felt no belonging, only anxiety. The other kids called me names and pushed me. Both the girls and the boys did it. The teachers didn't care. It was easier not to go to school. During class, you were just anxious for the next break. That did not make you ready to learn.

Being Tater wasn't acceptable in those days. As a people, we were not accepted. It was OK to harass us – racism at its worst. This was everyday life for us, but it has left its mark. You become sceptical and always wonder if people mean what they say or if they’re just pretending. These thoughts follow you.

As an adult, I tried to start school. I wanted to educate myself. I went to the employment office. Then they first wanted me to take an intelligence test to see if I was capable of learning. When I passed, they said I was too old. I would have liked to be a social worker or something within social services. You meet your own people in many situations, and I'd love to be there to help.

My parents also wanted me to get an education; at the same time, they were afraid to send me to school. They didn't want me to go somewhere where I would have a hard time. We didn't dare complain. It would be the same as admitting that you had done something wrong. Then it would have been reported to the Mission, which could lead to me being taken. The fear of being taken was also a big reason why we moved around so much.

I often went trading with my mother. We travelled a lot, and we went to trade in different villages in Telemark and Gudbrandsdalen. We were in Setesdal a lot. The people in Telemark loved trading."

Marriage and work

"I got married when I was 18. After I moved out, my father lived all over. He sold our house to my brother, then bought another house that he sold to my other brother. After he had a stroke and couldn’t walk, he went to a nursing home in Gjesåsen, but did not like it there.

My mum was my husband's father’s cousin, meaning my husband and I are second cousins. He was from Solør. I was 16 the first time I met him. We became a couple, which was the same as marriage at that time. We didn't get married until after we had our second child. We got married because of the children and had already been together for a few years, so we just thought a big wedding was stupid.

At first, we rented a house, then we built the one I still live in. I've lived here for 43 years. After we got married, we rented a house at Skotterud for two years.

I had five kids. We didn't get running water until the fourth child was born. We had an outside toilet. We lived next to a river. The kids built a cabin and made a raft for the river. They looked after each other, so that went well.

The laundry was done inside in the winter and outside in the summer. I boiled clothes on the primus. I also had a washboard. Washing clothes took a whole day every week. I started in the morning and kept on all day. Then it was all hung on long clothes lines.

Life changed in every way when I had children. I was 19. My husband didn't help much with the kids. It wasn't his job; it was mine. I really connected with the kids, but with so many kids it's no use discussing everything. I was the one who set boundaries and the kids knew a no was a no. At the same time, I also gave the kids freedom. I always had a reason for the boundaries.

The kids also helped at home. The youngest one often said, ‘if I get five kroner, I will do the dishes.’ The eldest was very good at saving. He sometimes got some money from his uncles and aunts. He saved it and gave it to me when we had little money. He had – and still has – such a caring heart. My oldest boy was my nanny. His sister was wild, while he was calm and small for his age. When he was afraid that his little sister would go out into the road, he sat on her so she couldn't go anywhere.

For a long period of time, my health was poor. Then the kids did the shopping for me. I wrote a shopping list that they gave to the butcher. The kids were all under school age then. The butcher tied the goods to the kids’ chair sledge. My husband was away at work all day, so the kids helped me. I didn't think it could be any different. I was young and stupid when I got married. You don't get to know a person until you've been together for quite some time and have children together.

As for the kids, I've always tried to lead by example. A kid notices that you say what you mean. I've never told the kids not to swear, but they don't. I remember one of my daughters swearing once and being horrified that she did.

Respecting older people is something I've taught them, like getting up when they arrive so they can sit down. Being polite and not being rude. I don’t like rudeness.

I think Tater people care more about this. It was important to approach people a certain way when you were trading. Therefore, being considerate is something we learned at an early age. We had to survive."

Children's schooling

"When my eldest son was eight, both he and his sister, who was 11 months younger, started school. He didn't want to go alone, so his sister started at the same time.

The school years were very tough. The first two years went smoothly. Then there were problems. Being a Tater was tantamount to being a bully victim. They say little pitchers have big ears. The kids pick up on what is said at the dinner table and take it with them. It wasn't just bullying; it was a kind of warfare. The oldest had to look after the youngest, so he often had to sort it out!

It went so far that, when my eldest son Holger was an adult, the principal at the school where my kids had gone apologised to him for the treatment they had received. If there is not a proper environment at school, then anything goes. Only once did a pupil stand up for Holger. That was in high school.

The kids were punched and kicked. In one incident, they were locked in the boiler room at school because it took them too long to pick up a book. Another time, the teacher took away my daughter’s maths books. Their education suffered. They wanted to keep going because they wanted an education, but it just didn't work out. In high school (business school), Holger got top grades. Although he was unable to finish, at least he was able to show that he wasn’t stupid. He was good at maths, too."

Family and work

"The boys did tinsmith work with their father, while the girls eventually got cleaning jobs at Ullevål [Hospital]. Then they got boyfriends and were married, and that was the end of their careers.

I wish they all had a profession they enjoyed. As for my girls, I see that one has a very caring side, while the other has trading talent! They have talents and abilities. But so much has been destroyed at school. They're doing well – that’s not what I mean. The youngest one works in a store now. She's gone trading with me a lot, which is not that easy today. There is so much being offered now. The oldest boy worked a lot with his father."

Trading

"In the spring we always went travelling. My husband was doing gutters and I traded a little bit. If spring came early, we left. We lived in tents. It was cumbersome, but at the time that was all we knew. We always asked the farmer if we could camp in his field. Then we always had access to water, either next door or from a stream or a river.

The first time we stayed at a camping ground was when I had Mariann, our third child. It's more than 50 years ago now. When she was two days old, it was right back to the tent. We had a six-man tent. Mariann was born in June. Sleeping in tents and being on the ground was a good experience. Then you’re alive. When washing clothes, you sat down with the washboard and carried the clothes down to the river.

We still travel every summer, but we stay at campgrounds. Sometimes we all travel together, with our children and grandchildren. When we went trading, we went to the places where we felt welcome. At school it was different. We had no say in who we had to be with there.

When the kids were small, I was a housewife and a trader. The kids were always with me. When we were on trade trips, they were calm and quiet. They knew that, in order to put food on the table, they needed to be calm. As they got a little older they helped me. My husband was doing roof work, tinsmith work and antiques. When we were trading antiques, we worked as equals. We helped each other with restoration, lifting and carrying.

I sold everything from tablecloths to fire ladders, gutters, and work clothes. The bags that were full of clothes were heavy. I ‘knocked on doors’ and also had a stand. I built up routes where people were friendly. Many people say they miss door-to-door trade and that we should start a project to get young people to continue this tradition so that it does not disappear.

Sometimes I earned nothing on a trade and other times I could earn a thousand kroner. You barely survived.

My husband was a good worker and was well liked in the village. He earned a lot more than I did. I administered our finances. I kept all the money and gave him pocket money. That's how it was back then. It is common in our culture that the women run everyday life. They are observant and it's no use trying to fool them. The men are mostly out trading and decide what to do workwise."

Work and association work

"As I mentioned, my first job in life was at Globus. I was divorced when my eldest son was 23. Then he told me I should try to get a cleaning job. I called Vaske Bakke’s company in Oslo to and got a job the same day. Only my youngest daughter lived at home then. I commuted to Oslo every day for work for two years. Then I became ill, and eventually the doctor said, ‘this is no good’, so he gave me a sick note. A little while after that, he thought I shouldn't work anymore, and I began to receive disability benefits. That wasn't much to get by on.

Then I started at the Gospel Centre. I only worked for petrol money. I needed to be doing something. I did this for two or three years, but the doctor thought this was not good for me either, so I stopped.

After I left the Gospel Centre, I became active in the Romanifolkets Landsforening (RFL), which is now called the Taternes Landsforening (TL) [the Tater National Association]. I saw how important it was for us to organise ourselves to stand up for our rights. Whoever has lived the Tater life on the road knows best what the needs are. I felt it was time for us to speak up for what we want.

I joined the organisation after Leif Larsen, who started it, visited us. He explained what it was. I wasn't very keen to join. The authorities were viewed with scepticism, so we understood that we had to do something ourselves.

When I joined, I had already stopped trading due to poor health. Taternes Landsforening works for the Tater people’s rights in general. We have had many meetings with the ministries and took the initiative to establish the Tater/Romani People’s Cultural Fund, which the authorities later closed down.

Our organisation has also been key to the establishment of Latjo Drom at the Glomdal Museum. At first it was quite frightening to be at meetings both in the ministries and at the museum. You felt a bit like Solan Gundersen: ‘Is this for real?’ I often had to pinch myself to understand that it was true.

In our family, we've never hidden our origin, so all the kids thought it was fine that I had started working for the Association. Two of them also participate. Amongst the projects I am proud of being involved in is a school project that we initiated in cooperation with Queen Maud University College. This is something I think is important. Enabling the Tater to use e-learning when they are out trading. The kids are the future."

Sense of belonging and children's education

"I've lived in the same place for 43 years. Before that, I lived in many different places. I like not having to travel. I never had a childhood home. I wanted my children to have a place where they belonged and where they could create childhood memories. A place they could come back to when summer was over. The law also stated that when you settled somewhere, you got a right of municipal domicile and were no longer a ‘tramp’. That law was in effect when my kids were growing up.

I had decided that my children should be allowed to go to just one school, which has paid off. The children who bullied my children have regrets today and understand that bullying is not okay. Their children don't bully my grandchildren, so my grandchildren are doing fine at school.

Eidskog has received immigrants as well. That probably makes it easier for us. Today, people also travel more. A man from India who lives here told us we should probably live in France. They speak loudly and gesticulate there, just like us.

This man from India was a doctor here in Eidskog. I could go to him in the middle of the night if the kids were sick. I often didn't have to pay for the consultations. Sometimes it probably went a little too far. Once when I went to him in the middle of the night, he said to me, ‘Your children are not sick. You're the one who's sick. You're going to kill me!’. He advised me to use anise against colic pain in infants. You drink it and the child's pain goes away."

Life today and expectations for the future

"I have my own house, but I almost have to ask my children and grandchildren for some time to myself. It is a very natural way of life for us that grandparents, children and grandchildren spend a lot of time together. There is something about the unity that we cannot rid ourselves of. Young people wanting to be with the elderly in daily life may be a bit odd. In the past, this was necessary to survive; perhaps there is something in the genes we are unable to shake off. We always know where everyone is.

Today, a lot of things are different, but a lot is also the same. Not too long ago, I heard an interview on the radio where an older Tater talked about life on the road. He said the Tater lifestyle will soon be gone. The customs change, the way we live changes, the way we speak changes, but I feel my people still has the values I appreciate. They shake hands nicely when greeting someone. It's with some concern I see things changing, but I guess it may last for another generation. I guess in the future everyone may have a permanent job, but we can still protect our culture, our language, the crafts and the fact that we appreciate each other and the unity, so I'm pretty optimistic. The younger generation is very conscious that we should preserve the culture and that it is fun to be together. The fact is that we love each other and don't sit in our own houses and sulk.

I don't think I could have been married to a ‘buro’ [farmer or resident - one who is not a Tater]. He would have had to be a very special man. It has something to do with mentality. Something about understanding each other. I only have ‘buros’ as sons-in-law and daughters-in-law. We have a very good relationship, but there is something about the understanding, something about our look. It's very hard to explain. It was especially difficult with my first son-in-law. I tried to chase him away, but it didn't work, and he became like a son to me. We can socialise and we have a good relationship, but there’s something missing that I can't put into words."

Expectations for the future

"In a way, my expectations for the future have not been met; in a different way, they have been more than met. What I didn't expect was that I'd have an incredibly rich life after I got divorced 22 years ago. I was able to grow as a person and got to know myself. I don't think I would have been able to do that within the marriage. The two lives have been completely different – the one I lived as a married woman and the one I live now. Then, I lived only for family, relatives and friends. Being married dominates your everyday life. My small world was enough for me at that time.

When I got divorced, the kids also started growing up and I had to find my own way. Then I got to know myself for better and for worse. I became good friends with the woman I found out I was!

If I have interpreted the reactions of the people I have met correctly, they have encouraged me all the way. I've been warmly received everywhere: in the rural environment where I traded; when I had a cleaning job; in the Association work that I have been doing for several years, and in the meetings with the ministries; at the College where we have had the school project; at the university during a language project, and at the Glomdal Museum where we have created exhibitions and where I worked for many years. This has done something for me. Maybe being alone is not that bad? You can make choices in life and stand by them. It's something worth showing the kids: that you don't give up when faced with adversity!"